A comment: Revisiting George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four in 2010

Since first appearing in the popular lexicon, the term “Orwellian” has conjured up a vision of the prototypical “totalitarian state”: a one-party dictatorship that swarmed with secret police, spied on its own people, quashed dissent, made arbitrary arrests, tortured prisoners, waged perpetual war, rewrote history for mere expedience, impoverished its own working population, and rooted its political discourse in doublethink—a thought system defined as “the power of holding two contradictory beliefs in one’s mind simultaneously, and accepting both of them.”

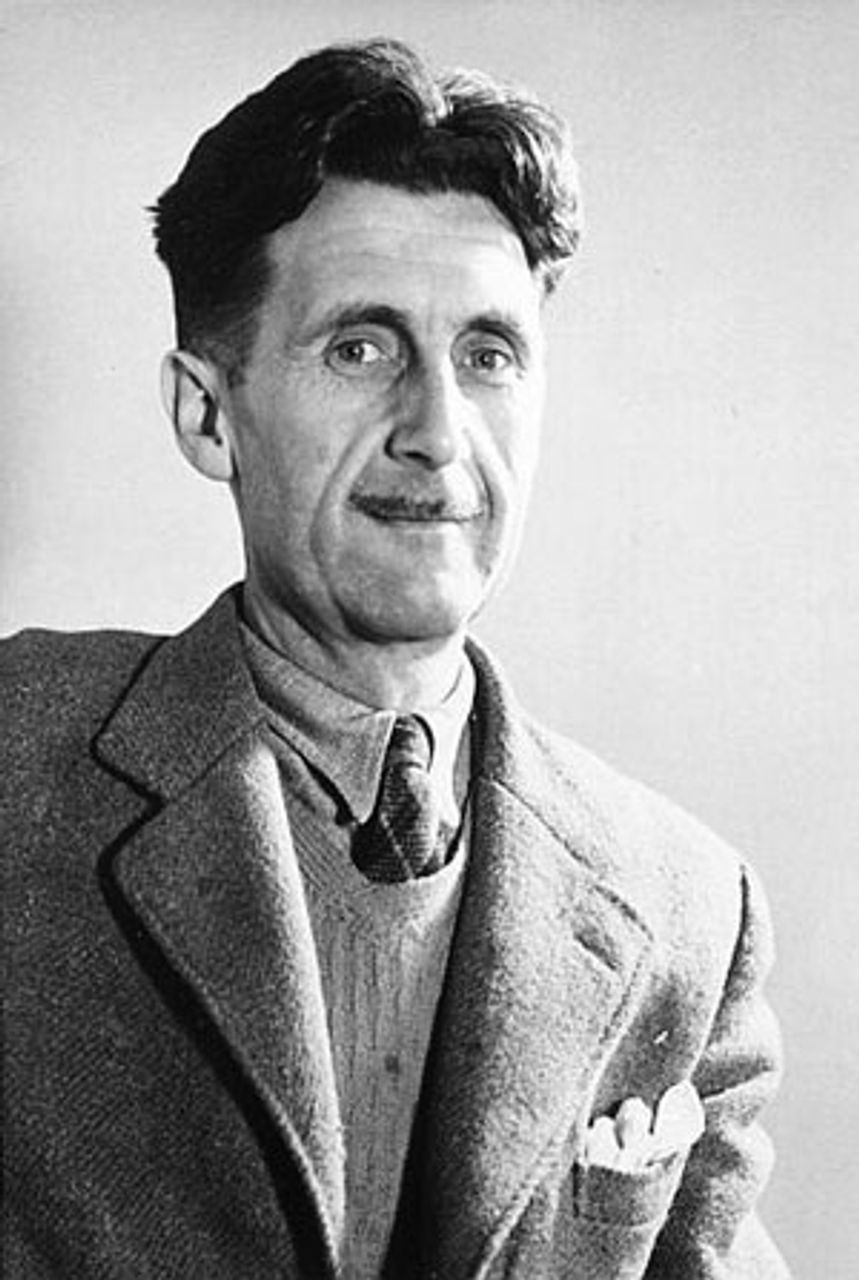

Many Americans would easily recognize this description of “Oceania,” the futuristic dystopia immortalized by George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, one of the most influential English-language novels of the mid-twentieth century.

Whether many Americans recognize that this description applies to their own society as well is another matter. But since the theft of the 2000 election—a period marked by such events as the 9/11 attacks, the invasion of Iraq based on fictitious “WMD” (weapons of mass destruction), the torture scandals, and the 2008 financial crash—it’s a point that increasing numbers of Americans seem to be grasping.

Nineteen Eighty-Four was published in June 1949, amid rising Cold War tensions. For most Western readers, the book was readily interpreted through the anticommunist prism of that period.

The novel’s police state bore an obvious resemblance to Stalin’s USSR. Coming from Orwell—a self-described democratic socialist who was deeply hostile to Stalinism—this was unsurprising. But while Orwell was too clear-sighted to conflate Stalinism with socialism (writing, for example, “My recent novel [‘1984’] is NOT intended as an attack on socialism…but as a show-up of the perversions...which have already been partly realized in Communism and Fascism.…”[1]), his Cold War-era readership was often blind to this distinction. His cautionary notes (“The scene of the book is laid in Britain…to emphasize that the English-speaking races are not innately better than anyone else and that totalitarianism…could triumph anywhere”) were largely overlooked, and in the public mind, the novel’s grim prophesy (“If you want a picture of the future, imagine a boot stamping on a human face—forever”) attached itself mainly to political systems seen as enemies of Western-style capitalist “democracies.”(2)

Yet Nineteen Eighty-Four was no endorsement of the West. It posits only an unaccountable elite that rules in its own interests and maintains power by taking state-run mind control to its logical extreme. It examines what’s operationally involved in compelling a population to submit to exploitative rule—without regard to the nominal form of economic organization. Put a bit differently, the book considers the psycho-social machinery of unaccountable state power in general—regardless whether it originates from a ruling bureaucracy or from finance capital. It explores the general problem of maintaining social stability in a highly unequal society, which can be done only through some combination of repression, and controlling the population’s consciousness.

Crude tyrannies rely primarily on repression. Sophisticated tyrannies find subtler means of controlling consciousness. Consciousness, in turn, is deeply intertwined with a society’s public use of language. Oceania and America are sophisticated shapers of consciousness. This is why the two societies increasingly share core characteristics, and why Nineteen Eighty-Four has arguably even more relevance for readers in 2010 than it did during the Cold War—when it was already recognized for its keen insights into the connections between language, consciousness, conformity and power.

Mind control in Oceania, 1984

In Orwell’s fictional Oceania, the psychosocial machinery worked roughly like this: all power was held by The Party. Perpetual war was the mainspring of state policy. The media was a simple conduit for state propaganda. The population was held in check by constant surveillance, enforced by the Thought Police; and also by development of a new language, Newspeak, whose express purpose was narrowing the range of thought so that thoughtcrime (unorthodox thought) was in principle rendered impossible (since the language itself lacked the constructs needed for formulating heretical thoughts).

The state devised rituals, such as public hangings of prisoners and the Two Minutes Hate, to generate enthusiasm for crude nationalism and bellicose chauvinism. The “proles”—85 percent of the population—were flooded with mind-numbing media diversions (focused mainly on sports, crime, the Lottery, and sex) to prevent them from developing political consciousness. The proles were thus kept “without the power of grasping that the world could be other than it is.”

Party members, meanwhile (both of the Inner Party, which was less than 2 percent of the population; and of the Outer Party of lesser functionaries), had to master the art of doublethink to avoid committing thoughtcrime. A Party member was “supposed to live in a continuous frenzy of hatred of foreign enemies and internal traitors, triumph over victories, and self-abasement before the power and wisdom of the Party.” Those unskilled at self-regulating their thoughts, and who thus posed a potential threat to orthodoxy, were systematically culled from the population. Recalcitrants were tortured in ways scientifically designed to crush their humanity.

How it works in the USA, 2010

Every one of the above-named features is recognizably present in American society in 2010—some in full-blown form; others in more primitive (and still evolving) form. An exhaustive list of the many modern-day parallels would fill an entire book. Such a book would include such minor correspondences as the fact that Oceania’s ironically-named “Ministry of Peace” is no more Orwellian a euphemism than the US “Department of Defense.”

It would include more substantial parallels, such as the many ways in which the US media function as a kind of Newspeak, systematically attempting to deprive the population of the concepts and perspectives required for developing “unorthodox thoughts” (i.e., rational critiques of the existing politico-economic system). It would include the logic underlying the Wall Street bailout, which is essentially that the global financial crisis should be paid for by the victims of that crisis, while the perpetrators of the crisis should be indemnified against loss; and that this policy should be imposed on the victims (i.e., almost the entire population) by a government they “democratically elected.” (Marx: “The oppressed are allowed once every few years to decide which particular representatives of the oppressing class are to represent and repress them.”)

Sketched below are some of the parallels underscoring how far we’ve come in the few decades since Orwell’s vision was considered a futuristic fantasy; and since the West’s forms of limited capitalist “democracy” were considered bulwarks against Oceania-style tyranny.

It should be noted that Orwell had in mind conditions under which the working class had suffered a historic defeat, in the case of fascist Germany or Italy, or had power usurped from it by a counterrevolutionary bureaucracy, in the Soviet Union. In the US today the official view of things is increasingly contested and rejected, even if that often still occurs in a confused manner. Certainly, as far as the authoritarian aims and ambitions of America's rulers are concerned, nothing in Orwell's conception would have to be modified.

- Perpetual War: Like Oceania, today’s United States exists in a state of perpetual war—a condition accepted as “normal” in both societies. Former US Vice President Cheney said in 2001 that the US War on Terror “may never end. At least, not in our lifetime”—a remark that elicited no outcry from either big business party, nor from the corporate media. To this day, the remark has gone unchallenged. The issue of perpetual war wasn’t deemed important enough to be mentioned (let alone debated) in any of the four national elections since Cheney made that assertion.

- War for Maintaining Society’s Class Structure: Speaking through his character “Goldstein” (loosely based on the historical figure of Trotsky), Orwell wrote, “The war is waged by each ruling group against its own subjects, and the object of the war is not to make or prevent conquests of territory, but to keep the structure of society intact.” He continued, “But in a physical sense war involves very small numbers of people, mostly highly-trained specialists, and causes comparatively few casualties.... And at the same time the consciousness of being at war, and therefore in danger, makes the handing-over of all power to a small caste seem the natural, unavoidable condition of survival.”

These remarks are quite applicable, respectively, to the US “War on Terror”; to the use of so-called “Special Forces” and “predator drones”; and to the relentless associated fear-mongering and demonization campaigns. Scarcely a word needs to be changed, with the exception that the US war is indeed aimed at territorial gain—namely, domination of regions that are oil-rich, or of strategic value for pipeline routes and/or military bases. This exception in no way invalidates Orwell’s points that “the object of the war is [at least in part] to keep the structure of society intact” and that “The war is waged by each ruling group against its own subjects.”

- The One-Party State: Like Oceania, the US is virtually a one-party state. Its two big business parties are falsely presented as two “opposing” parties. In reality, they are little more than soft-rhetoric and hard-rhetoric factions of the one real party—the financial aristocracy—that has unchallenged sway over all matters of economic significance and resource deployment. The US variant of the one-party state is actually more dangerously Orwellian than Oceania’s variant, because it superficially appears to be something it’s manifestly not. Oceania, at least, was “honest” enough not to bother with the pretense of democracy.

Americans have been conditioned to accept the limited, mostly rhetorical differences between Republicans and Democrats as “evidence” that the US is a “democracy.” The march of events is relentlessly exposing the grievous deficiencies of this thesis, but its broad general acceptance over the years (taking into account as well the residual strength of American imperialism and the role played by the AFL-CIO and various “left” forces) testifies to the official political culture’s power to dominate and mold mass consciousness. (Marx: “The ideas of the ruling class are in every epoch the ruling ideas.”)

- Media as a Conduit for State Propaganda: As in Oceania, today’s US media are essentially conduits for state propaganda. A brief examination of the news coverage of the last decade’s major events would amply bear out this characterization, and every passing day provides innumerable examples of this behavior. Oceania’s telescreen constantly touted increases in pig iron production and chocolate rations, mixed with triumphant reports on the glorious victories won by “the heroes on the Malabar front.”

There is little essential difference between this and the fare of American news programs (except perhaps for the existence of advertisements, whose forced cheeriness makes for a merrier tone than that heard on Oceania’s bleak, martial “newscasts”). In 2009, the US media expressed uniform “outrage” about an allegedly stolen election in Iran. No serious evidence was offered to support allegations of the election’s theft; and none of these same media outlets had even acknowledged (let alone were outraged by) the blatantly stolen US presidential election of 2000. (In fact, they unanimously hailed the 2000 election outcome as proof that “the system worked,” on grounds that power was transferred without violence—in other words, that elites were able to steal the election without resistance from the citizenry.)

- Surveillance: On page 2 of the novel, we are introduced to the Thought Police. “How often, or on what system, the Thought Police plugged in on any individual wire was guesswork. It was even conceivable that they watched everybody all the time.” Since about 2004, these surveillance functions have been implemented in the US by institutions such as the National Security Agency, with its massive eavesdropping on the private communications of American citizens. This issue was not mentioned in any of the three national elections since 2004, and the New York Times (complying with a request from the Bush administration) deliberately spiked a report on the NSA eavesdropping programs prior to the 2004 election. The newspaper finally “reported” it more than a year later (just before publication of a book on the subject by James Risen, the Times reporter whose story the paper had suppressed).

- Elite-Driven Cultural Crippling of Mass Political Consciousness: Orwell’s vision of using mass culture as a tool for crippling the population’s political consciousness has been realized in the efforts of the American ruling elite. He named the main mind-numbing diversions as the Lottery, and “rubbishy newspapers containing almost nothing except sport, crime, and astrology, sensational five-cent novelettes…films oozing with sex…(and) the lowest kind of pornography.” He overlooked such important categories as celebrity gossip and stock-market chatter, but was in principle squarely on the mark. A population that reads celebrity magazines and watches entertainment TV is far less prepared to understand the social forces responsible for its declining living standards, and thus less able to defend itself.

- The Cult of the Leader: The novel is set in the drab London of the “future”—April 1984. Orwell’s protagonist, Winston Smith, lives in a crumbling apartment building that’s named “Victory Mansions” and smells of boiled cabbage. Prominently displayed on the building’s every landing is a large colored poster depicting “an enormous face…of a man about forty-five, with a heavy black moustache and ruggedly handsome features.” In 2010, one can hardly read of the ubiquitous Big Brother posters in a grim dilapidated London, without thinking of the “Barack Obama Hope” posters, visible throughout today’s decaying American cities.

Big Brother is described as “the guise in which the Party chooses to exhibit itself to the world. His function is to act as a focusing point for love, fear, and reverence, emotions which are felt more easily towards an individual than an organization.” This passage captures the essential PR strategy used to sell Obama—the candidate of Wall Street—to US voters in 2008. Indeed, Obama’s whole campaign was designed to exploit the idea that emotions like love and hope “are felt more easily towards an individual” than towards organizations—such as the banks, whose interests he essentially represents.

- “Who Controls the Present Controls the Past….”: Winston works in the Ministry of Truth, whose mission is the “day-to-day falsification of the past…[which] is as necessary to the stability of the regime as the work of repression.” Oceania’s Ministry of Truth functions have been implemented by the US corporate media, which demonizes groups like Al-Qaeda and the Taliban on a round-the-clock basis, while carefully “forgetting” that both these groups were weaned and nurtured on millions of dollars of CIA funding in recent decades. Such inconvenient facts are regularly jettisoned down the memory hole because they no longer harmonize with state policy. The facts must therefore be modified to make them “correct” in the context of the present. (As the head of British MI6 paraphrased Bush in 2002 regarding “WMD” and the planned invasion of Iraq: “the intelligence and facts were being fixed around the policy”). Just as Oceania was one day allied with Eastasia and the next day at war with Eastasia, the US is one day at war with Saddam Hussein and Islamic fundamentalism, while in the Reagan years, was aggressively supporting both. (Reagan called the mujahedeen in Afghanistan “freedom fighters” and the “moral equivalent of the Founding Fathers.”)

- Public Rituals for Demonizing State Enemies: The “Two Minutes Hate” is essentially what happens on American television whenever names of official enemies like Saddam Hussein, Hamas, Ahmadinejad, Castro, and Hugo Chavez are mentioned. This occurs in its most blatant form on explicitly right-wing outlets like FOX News and the Wall Street Journal Op-Ed page, but is no less present in the supposedly “liberal” outlets, where the blatancy is toned down but the viewpoint is substantially the same. The hanging of Hussein was greeted by the US media with the same breathless, panting bloodlust as Oceania’s public hangings. “Did you go and see the prisoners hanged yesterday?,” Winston is asked by his colleague Syme, sitting down to lunch one day in the ministry canteen. This scene doubtless had its counterparts across the US, when Hussein was executed in December 2006.

- Bombing Civilian “Enemies” as Entertainment: Winston goes to the movies on page 7 and sees a war newsreel; he notes in his diary that the audience is “much amused” by footage of helpless civilians being blown to pieces by Oceania’s helicopter gunships. Broad swaths of American TV programming, movies and video games attempt to feed on, and encourage, the same base instincts.

- A Political Culture Cloaking Itself in the Virtue of Its Opposite: “Goldstein” observes that “the Party rejects and vilifies every principle for which the Socialist movement originally stood, and…[does so] in the name of socialism.” This was Orwell’s thoroughly justified assessment of Stalinism in 1949. The passage suggests its modern-day analogue: “the US government undermines or eviscerates the substantive essence of democracy, and does so in the name of democracy.”

- Police Intimidation of Citizens: Oceania’s most fearsome and physically imposing government ministry, the Ministry of Love, is guarded by “gorilla-faced guards in black uniforms, armed with jointed truncheons.” The real-life counterparts of these guards appear at US political conventions and outside WTO meetings, clad in Kevlar, menacing, shoving, or even beating unarmed protestors with truncheons. The media regularly describe the protestors as “hoodlums” and “anarchists,” while approvingly citing Iranian protests against Ahmadinejad or Venezuelan protests against Chavez as examples of “legitimate dissent.” (Speaking of “Orwellian:” antiwar protestors who wished to demonstrate at recent US political conventions were placed in fenced-off pens topped with concertina wire, out of sight of the media and many blocks distant from the convention halls. These pens were called “Free Speech Zones”—with no irony intended.)

- Depravity and Dehumanization as State Policy: The novel is chillingly imaginative in its depiction of torture. At one point, the interrogator O’Brien rips out one of Winston’s rotting teeth with his bare hand, to show Winston how futile and pathetic his resistance is. Then follows the famous climactic torture scene in Room 101, where the rat-cage mask is placed over Winston’s head. A present-day reader might immediately think of the “insects” variation revealed in the recent US torture memos, where “stinging insects” were released into a closed box containing a helpless and terrified prisoner. But even this falls short of the full scope of US torture methods, which have included rape, sexual humiliation, and deliberate offense of religious beliefs, as in draping women’s panties covered with menstrual blood over Muslim prisoners’ heads. When it comes to depravity and torture, even the adjective “Orwellian” doesn’t quite do justice to the ingenuity of the US military-intelligence apparatus.

Class consciousness and social equality

Orwell’s book was enthusiastically received in the US. Two weeks after its publication, Time called it his “finest work of fiction,” but construed it primarily (along with Animal Farm) as an attack on “Communism.” (3) Orwell, however (as alluded to earlier), meant both books as warnings about trends in Western democracies as well. The book’s warm reception in the US was somewhat paradoxical, since it presented a clear and compelling class-based analysis of the driving forces in society. This perspective defied the emerging political norms of 1949, when class awareness was in the process of being systematically expunged from permissible American thought. The novel’s apparent “anti-Communism” may well have protected it from a backlash against its class-consciousness—which was certainly a thoughtcrime in the US of 1949, and remains one today.

Winston had a decidedly sympathetic and hopeful attitude towards the “proles.” At least four times, he said the proles were the only hope for the future, describing them in terms like these: “if there was hope, it MUST lie in the proles, because only there, in those swarming disregarded masses, eighty-five per cent of the population of Oceania, could the force to destroy the Party ever be generated.” The proles, Winston believed, “if only they could somehow become conscious of their own strength…needed only to rise up and shake themselves like a horse shaking off flies. If they chose, they could blow the Party to pieces tomorrow morning.” The Oceania ruling stratum had succeeded in crushing Party members’ feelings of interpersonal solidarity, while “the proles had stayed human. They had not become hardened.” They had a “vitality which the Party did not share and could not kill…the future belonged to the proles.”

Winston reflects that “where there is equality, there can be sanity”—a point of singular relevance to an America characterized by skyrocketing social inequality. The relation between social hierarchy and the distribution of wealth is limned in these terms: “an all-round increase in wealth threatened the destruction…of a hierarchical society.… It was possible, no doubt, to imagine a society in which ‘wealth’…should be evenly distributed, while ‘power’ remained in the hands of a small privileged caste. But in practice such a society could not long remain stable. For if leisure and security were enjoyed by all alike, the great mass of human beings who are normally stupefied by poverty would become literate and would learn to think for themselves; and when once they had done this, they would…realize that the privileged minority had no function, and…would sweep it away.” From the rulers’ viewpoint in a highly unequal society, this is a dangerous and indeed, subversive thought.

These are authentically radical ideas—unsurprising for an author who volunteered to fight with the POUM against fascism in Spain. In particular, the identification of the working class as the only genuinely revolutionary social force directly echoes Marx and Engels. The passage about the proles becoming conscious, rising up, and “like a horse shaking off flies,” blowing the Party to pieces—this graphically renders the idea of a mass uprising from below, resulting from a working class articulating demands conceived through its own awareness of itself as a class, with an independent sense of its own interests.

Training the population in “doublethink”

Winston reflects that “the world-view of the Party imposed itself most successfully on people incapable of understanding it. They could be made to accept the most flagrant violations of reality, because they…were not sufficiently interested in public events to notice what was happening.” And a bit later: “Even the humblest Party member is expected to be competent, industrious, and even intelligent within narrow limits, but it is also necessary that he should be a credulous and ignorant fanatic whose prevailing moods are fear, hatred, adulation, and orgiastic triumph. In other words it is appropriate that he should have the mentality appropriate to a state of war.” It would be hard to find a more accurate description of the attitudes encouraged by modern-day America’s official political culture.

The full definition of doublethink is: “The power of holding two contradictory beliefs in one’s mind simultaneously, and accepting both of them.… To tell deliberate lies while genuinely believing in them, to forget any fact that has become inconvenient, and then, when it becomes necessary again, to draw it back from oblivion for just so long as it is needed, to deny the existence of objective reality and all the while to take account of the reality which one denies—all this is indispensably necessary. Even in using the word doublethink it is necessary to exercise doublethink. For by using the word one admits that one is tampering with reality; by a fresh act of doublethink one erases this knowledge; and so on indefinitely, with the lie always one leap ahead of the truth.”

This passage characterizes the official versions of the signal events in US politics since the Supreme Court appointed George W. Bush president in the 2000 election. Virtually every major event since that time was presented to the public on the basis of doublethink.

For example, within months of the Iraq invasion, the US media were forced to acknowledge that there were no WMD after all. But this fact was presented as though devoid of meaning or consequence. Media accounts casually dismissed it as matter of “flawed intelligence.” Applying such a phrase to a major war crime (as defined at Nuremberg) is doublethink because on the one hand, it acknowledges error. But no sooner is error acknowledged than two new lies are introduced: that the intelligence error was only very slight; and that only the exactitude of US intelligence was at issue (“the lie always one leap ahead of the truth”).

Acknowledging the non-existence of WMD while defending the general character of the war (the job of US officials and media spokesmen) is another instance of doublethink, since a war can hardly be justified when the stated reason for waging it is false. One can hold both beliefs simultaneously only by juggling them—momentarily banishing one belief to oblivion while discussing the other.

In the novel, the interrogator O’Brien famously holds up four fingers and demands that Winston see five. This demand does no more violence to logic than Obama’s position on torture, expressed in his May 21, 2009, speech from the National Archives. Posturing as a champion of the Rule of Law, and standing next to the original parchment of the US Constitution, Obama declared that torture is wrong; that we must uphold our constitutional values; that “We do not torture”—then added that US officials who ordered torture will not be prosecuted for it, and photographs documenting US torture would be withheld from the public. He proceeded to defend “extraordinary renditions,” and to propose the medieval policy of indefinite “preventive detention” in the same speech.

“War is Peace”

Accepting the Nobel Peace Prize on December 10, 2009, Obama continued in this vein, at an event incisively reviewed by the WSWS, and fairly described as an unsurpassably Orwellian spectacle. The commander-in-chief of history’s most grotesquely bloated war machine, currently in the midst of two wars of aggression (one that he himself had sharply escalated) and head of an administration whose chief diplomat has threatened Iran with “annihilation,” was honored as the world’s outstanding peacemaker. Opening his remarks with the most perfunctory possible nod to “the creed and lives” of Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr., Obama pivoted in the next sentence to dispatch any illusions that his own foreign policy would be informed by their philosophy. (“But as a head of state sworn to protect and defend my nation, I cannot be guided by their examples alone.”)

The US president then plunged directly into a full-throated defense of state violence (provided, of course, that it’s led by the United States). He intoned, “I believe that force can be justified on humanitarian grounds, as it was in the Balkans” (i.e., War is Peace). The president of the state that invaded Iraq in defiance of both world opinion and the UN Security Council claimed that neither his nation nor any other “can insist that others follow the rules of the road if we refuse to follow them ourselves.” The president of a state closely allied with the governments of Saudi Arabia, Egypt and Pakistan claimed “our closest friends are governments that protect the rights of their citizens.” The president of the nation whose military and CIA have overthrown dozens of democracies since World War II and replaced them with brutal dictatorships claimed “America has never fought a war against a democracy.”

With breathtaking sanctimony, he said, “Let us reach for the world that ought to be—that spark of the divine that still stirs within each of our souls.… Somewhere today, in the here and now, in the world as it is, a soldier sees he’s outgunned, but stands firm to keep the peace. Somewhere today, in this world, a young protestor awaits the brutality of her government, but has the courage to march on. Somewhere today, a mother facing punishing poverty still takes the time to teach her child, scrapes together what few coins she has to send that child to school—because she believes that a cruel world still has a place for that child’s dreams.”

This kind of rhetoric—deemed “eloquent” by the US media during the 2008 campaign—recalls Orwell’s observation that “political language …is designed to make lies sound truthful and murder respectable, and to give an appearance of solidity to pure wind.”(4) Obama’s “peace-keeping” soldier would presumably be a US (or allied) soldier occupying a country for the usual predatory reasons. The “young protestor” would naturally be protesting against a government regarded as an official enemy by Washington, such as Iran or Venezuela.

The “government brutality” Obama decries is doubtless not a reference to the violence and torture perpetrated against civilians either directly by US military and mercenary forces, or by US-backed puppet governments and other proxies. The “mother facing punishing poverty” is an abstract, theoretical mother, not one living “in the here and now” whose poverty results from concrete conditions—such as unemployment caused by outsourcing or by the Wall Street-induced financial crisis, or by the gutting of social services consequent to that crisis—i.e., from conditions imposed on the US working population by corporate America, with the support of the entire political establishment.

“In a Time of Universal Deceit…”

As “Goldstein” explains, “Crimestop means the faculty of stopping short…at the threshold of any dangerous thought. It includes the power of not grasping analogies, of failing to perceive logical errors, of misunderstanding the simplest arguments if they are inimical to Ingsoc [“English Socialism,” the official ideology of the totalitarian regime in Oceania], and of being bored or repelled by any train of thought which is capable of leading in a heretical direction. Crimestop, in short, means protective stupidity.”

Replace “Ingsoc” by “official US policy,” and the passage applies perfectly to the process via which the US media pretend to “discuss” issues of the day. For instance, “military aggression” is frowned upon by the US media, unless the US or its allies are the aggressors, in which case the action becomes stabilization, peace-keeping, or even liberation. One must master the art of not grasping analogies, to fail to see that US military aggression is “aggression.” Coups d’état are similarly frowned upon, unless of course the US supports the coup, in which case it becomes a democracy movement (the “color” revolutions, etc.). Similarly, torture becomes enhanced interrogation techniques, while civilian deaths become regrettable but unavoidable collateral damage, when caused by US policy or personnel. Far from innocent “euphemism,” such perversions of language reveal the essential character of the dominant thought-system in American political culture.

While being “re-educated” in the Ministry of Love, Winston “set to work to exercise himself in crimestop. He presented himself with propositions—‘the Party says the earth is flat,’ ‘the Party says that ice is heavier than water’—and trained himself in not seeing or not understanding the arguments that contradicted them. It was not easy.… It needed…a sort of athleticism of mind, an ability at one moment to make the most delicate use of logic and at the next to be unconscious of the crudest logical errors.”

A similar “athleticism of mind” is required to digest the logic of a proposition offered by Obama in a televised interview just before his inauguration. Asked if he’d appoint a special prosecutor “to independently investigate the greatest crimes of the Bush administration, including torture and warrantless wiretapping,” the Harvard-trained former constitutional law professor answered that he had “a belief that we need to look forward as opposed to looking backwards”—a principle that would preclude ever prosecuting anyone for anything (but which, one may be sure, will be invoked only for crimes committed by the US state, or by the financial oligarchy whose interests that state represents).

Early in the novel, Winston undertakes to commit a subversive act: he begins writing a personal diary. He wistfully addresses it “To the future or the past, to a time when thought is free.” Orwell has elsewhere been credited with “In a time of universal deceit, telling the truth is a revolutionary act.” Assaulted by the Newspeak of the US political class, we manifestly live in a time of universal deceit. We are all Winston Smith, and must look to revolutionary acts of telling the truth to light the way to a time when thought is free.

Notes:

(1) The Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters of George Orwell Volume 4 (“In Front of Your Nose”), 1945–1950 p. 546 (Penguin)[back]

(2) For analysis of Orwell’s political trajectory, see Vicky Short, and Fred Mazelis [back]

(3) Time Magazine, June 20, 1949 [back]

(4) “Politics and the English Language,” [back]